Dr. Semmelweis and the Power of Handwashing

In light of our current global health situation, let’s explore a pivotal moment in medical history through data visualization. The story centers on Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, the pioneer of handwashing in medical practice, whose discovery saved countless lives despite facing ridicule from his peers.

The Father of Hand Hygiene

Recently honored by Google’s Doodle, Dr. Semmelweis worked at Vienna General Hospital’s maternity clinic from 1846-1849. There, he faced a devastating reality: puerperal fever was claiming up to 40% of admitted patients. His revolutionary theory? Doctors were carrying “decaying matter” from autopsies to maternity wards during examinations. His solution was simple yet radical: mandatory hand washing with chlorinated lime.

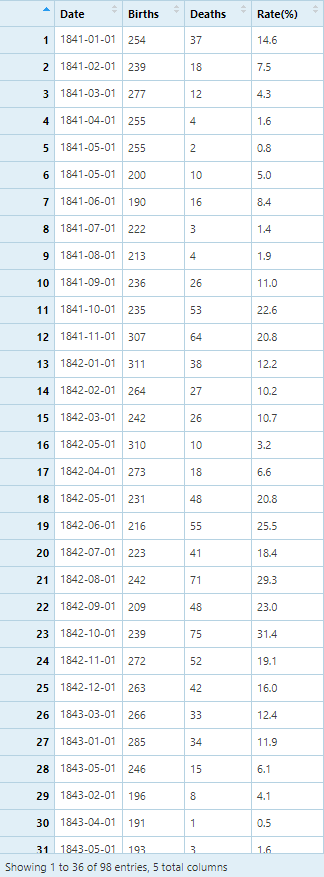

Analyzing Historical Data

Let’s examine the impact of his handwashing policy using data from Wikipedia. First, we’ll need to clean and prepare our data:

webpage <- xml2::read_html("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_mortality_rates_of_puerperal_fever#Monthly_mortality_rates_for_birthgiving_women_1841%E2%80%931849")

#get all the classes with tables

tables <- rvest::html_nodes(webpage, "table")

#get the first table of Vienna Hospital where Handwashing was started. This table is from the Dr. Semmelweis's primary clinic

vienna_hospital <- rvest::html_table(tables[grep("first clinic at the Vienna General Hospital 1841–1849",

tables,ignore.case = T)],fill = T)[[1]]

#clean the data by removing empty columns and chaning na in one row

vienna_hospital %<>% dplyr::select(-c(1,6)) %>% filter(!grepl('na', Births))

#change datastypes of everything but the "months"

vienna_hospital %<>% dplyr::mutate_at(vars(Births, Deaths,`Rate (%)`), dplyr::funs(as.numeric))

#changing to date is pretty tricky because we have both %B and %b

a <- readr::parse_date(vienna_hospital$Month, "%b %Y") # Produces NA when format is not "%B %Y"

b <- readr::parse_date(vienna_hospital$Month, "%B %Y") # Produces NA when format is not "%d.%m.%Y"

a[is.na(a)] <- b[!is.na(b)] # Combine both while keeping their ranks, ignore the warning

vienna_hospital$Month <- lubridate::ymd(a) # Put it back in your dataframe

colnames(vienna_hospital) <- c("Date", "Births", "Deaths", "Rate(%)")

Visualizing the Impact

Using ggplot2 with a historical theme:

#Apparently, from this date handwashing was made mandatory according to the Wikipedia Page

mandatory_handwashing_date = as.Date('1847-06-01')

#Added a TRUE/FALSE column to monthly called handwashing_started

vienna_hospital <- vienna_hospital%>% mutate(handwashing_started = (Date >= mandatory_handwashing_date))

#plot

line_plot <- ggplot2::ggplot(vienna_hospital, aes(x= Date, y = `Rate(%)`/100, color = handwashing_started))+

geom_line(show.legend = F, size= 1) +

labs(x = 'Year', y = '% monthly deaths', title = "Monthly deaths following the mandatory handwashing",

subtitle = "at the Vienna Hospital for the years 1841 to 1849",

caption = "*arrowhead & annotation were added with paint") +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::percent) +

scale_color_pomological()+ theme(plot.caption = element_text(size=8, face="italic", color="lightpink2"))

#Apply the theme & save

ggpomological::paint_pomological(

line_plot + theme_pomological("Harrington", 16),

res = 110)%>%

magick::image_write("handwashing_graph.png")

A Tragic Irony

Despite this clear evidence, the medical community rejected Semmelweis’s ideas. He died as an outcast in a mental institution, years before germ theory would validate his work. Today, his discovery saves millions of lives, especially relevant during our current health crisis.

Modern Day Relevance

As we face COVID-19, Semmelweis’s lessons are more important than ever:

- Wash hands thoroughly for 20 seconds

- Practice social distancing

- Help flatten the curve

- And please, stop hoarding toilet paper!

For more about Dr. Semmelweis and his work, visit the historical records.

Stay safe, maintain social distance, and remember: your actions can save lives.

NOTE: Found a mistake or have feedback? I’d love to hear from you - please reach out via email!